Svalbard. The hike

I’m always excited to share a new piece of writing and explain all about it. With Svalbard pieces, though, I’m protective, almost jealous of each word. I find it hard to let them go out ‘in the world’, because it means sharing something that sits at the very core of my heart. It’s like sharing a heartbeat. Yet it’s the one way I have to show the meaning of this unique place and ecosystem that so desperately needs protection and care. So here’s another one. It’s September 2024 and it’s my second time in Svalbard.

It’s past 4.30pm and I’m almost back at the hostel. I’m walking up the Longyear riverside, as I always do when I head back from town. I’ve been in Svalbard for four days now and tomorrow will be my last. Tomorrow, not today, though I can already sense the familiar ache irradiate from my chest. I wish I could savour the joy of being here at least while I’m here, but the sad longing for this place seeps through the cracks of my being in ways I cannot fight. I know it well.

Today I went on a hike with my favourite local tour company. It’s called Svalbard Wildlife Expeditions. If they have the trip I’m interested in, I’ll take it with them. They have a unique way to make you feel like you’re part of something, like you’re a regular there and you’re among friends. Every time I sit at the wooden table in their storage room for the pre-trip briefing, I recognise a familiar place. It felt that way from the very first time. It happened today too. We were a small group of six. We’d never met before, but the hike made us into a well-knit clique.

Around 11 we parked the van at Mine 7 just outside Longyearbyen and started uphill. Michael, our guide, asked if someone wanted to walk with his dog. I raised my hand, and the next thing I knew I had the leash around my waist, the other end tied to her harness. Ming and I were going to be together the whole day. ‘She will pull you to the front of the group’, Michael warned me, but I barely heard because we were already two metres ahead of everyone else.

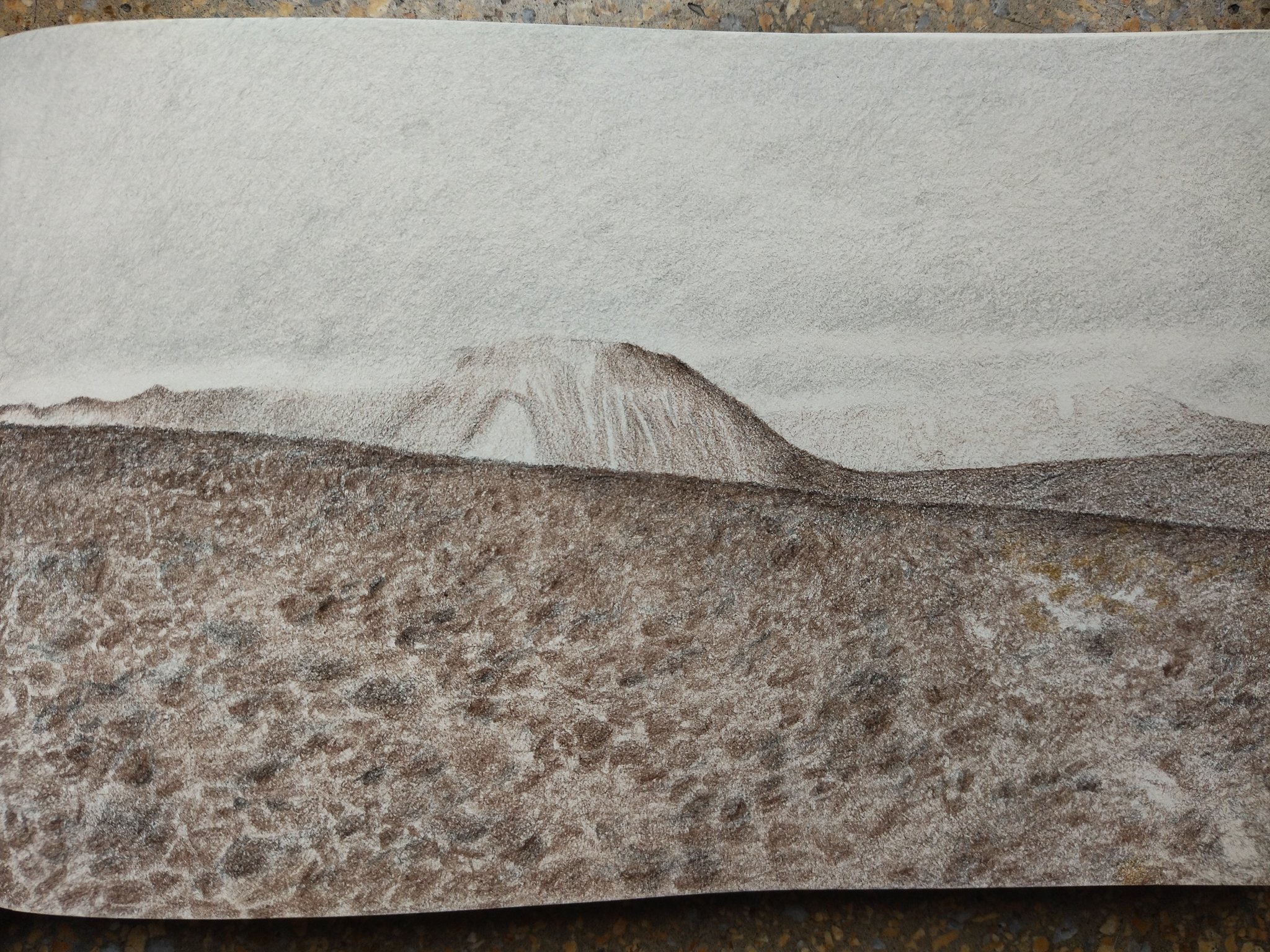

View from the Mine 7 area, at the start of the hike

Eiscat Svalbard Radar dishes above Mine 7. Adventdalen in the distance

The wind had been howling the whole night like an eerie omen, so we were prepared for it. It gave us no respite for the whole day. It made conversation impossible. All we managed were awkward, exaggerated gestures for directions and occasional instances of shouting. We left the path and headed up a slope of loose rocks. It was steep and raw. Ming’s effortless trot put my balance to the test, but I managed to keep upright. We made regular stops to wait for the others. When we reached the top, the gusts grew fiercer. There was no shelter. I took in my surroundings. I don’t recall ever comparing a landscape to the moon, but right then and there that was all I could think of.

I drew an imaginary straight line down the broad expanse of rocks and tried to walk it to its end. Ming attempted a brisker pace again, but by then we had a pattern in place. When she pulled forward, I leant my waist back into the rope. It felt like windsurfing. We stopped by the edge of the mountain and, as we waited for the others, we looked ahead. The glacier stretched out in front of us. It was ancient and immense.

The plateau

The glacier

When the others caught up with us, we attempted a few steps toward the frozen plain, but to no avail: it was too dangerous to venture on the ice. We kept to the edge of the mountain for a little longer. Then Michael called us over. The wind was soon going to pick up, so we had to be conscious of time.

We retraced our steps up the rocky plateau, back to the cairn we’d passed on the ascent. The wind blew from behind, so we sat in an orderly row and ate our lunch. We shielded our thermoses and food packs as best we could. A waft of Asian curry filled the colourless Arctic air. It felt surreal, but only for a moment. It felt right.

We took no breaks on the way down. Ming’s pull was gentle. Maybe she sensed we were nearing the end and she wanted to delay it for as long as she could. I could relate. Despite our best efforts, we were all back on the main path in no time. That’s when the clouds parted and the sun came out. It appeared like the epic hero you don’t expect anymore, a distant memory of something you once knew but were on the verge of letting go. The sunlight tinged the mountains all around in a golden hue. As I matched Ming’s pace downhill, I could see the weak outline of our shadows on the gravel. On the last stretch of path we burst into a run, all the way to the van.

The sun was a welcome sight, but I hadn’t missed it. The Arctic had gifted me with a blanket of impenetrable clouds, a windswept slippery route, a scenery drained of all colours. No room for the sun on a day like this. I thought back to Christiane Ritter and the memoir she wrote after overwintering in Svalbard with her husband in 1934. ‘I feel that I am close to the essence of all nature’, she wrote. I felt it too.

This place speaks to my soul in a way no other ever has. I measure the years by the time that spans between one Svalbard trip and the next. A never ending wait. Being here is like reaching down to the depths of the Earth. Table mountains sculpted in layers over millions of years. Valleys and fjords shaped by glaciers and rivers through centuries of carving and melting. Flowers the size of a pebble sprouting like droplets of colour in a boundless ocean of grey.

This place is the answer to a question I never had to ask.

A special thank you to Svalbard Wildlife Expeditions and our guide Michael for a memorable trip. And thank you to Ming Ming for never leaving me behind.

All opinions shared in this post are my own and my own only. I’m not getting paid for making promotional statements, I’m simply voicing my genuine thoughts.